Predicting a patient’s drug response requires more than identifying which genetic variants they carry. It also requires knowing how those variants are arranged across each chromosome. This organization, known as haplotype, determines how drug-metabolizing genes function in practice and directly shapes medication efficacy, toxicity risk, and dosing requirements. Pharmacogenomics (PGx) uses this haplotype information to move beyond population averages and enable truly individualized prescribing across oncology, psychiatry, pain management, and other therapeutic areas1,2.

In principle, full-gene pharmacogenomic testing transforms a routine blood draw into a functional blueprint of drug metabolism. In practice, however, many of the most clinically important pharmacogenes, such as CYP2D6 and DPYD have complex genomic architectures that challenge conventional sequencing approaches. Extensive structural variation, repetitive elements, and homologous regions frequently disrupt short-read analyses, obscuring haplotype structure and limiting confidence in clinical interpretation3,4.

This disconnect between variant detection and functional interpretation highlights a central limitation of current PGx testing and it is where long-read sequencing becomes transformative. In this article, we examine key pharmacogenes, highlight the limits of short-read approaches, and explain how long-read sequencing improves drug response prediction.

Why Full-Gene Variant Mapping Is Essential for Drug Response Prediction

At its core, full-gene pharmacogenomic testing seeks to capture all relevant variation within a gene, determine how those variants co-occur on each chromosome, and how they impact drug metabolism. Because drug metabolism is rarely dictated by a single variant in isolation, PGx reflects the combined effects of multiple variants acting together within the same haplotype. This principle is especially clear in pharmacogenes where multiple variants across the gene collectively determine enzyme activity and patient risk.

DPYD: Predicting Chemotherapy Toxicity Requires the Full Picture

The DPYD gene encodes dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD), the enzyme responsible for metabolizing fluoropyrimidine chemotherapies such as 5-fluorouracil and capecitabine. Spanning nearly one million base pairs and harboring more than 1,700 known variants, DPYD exemplifies why partial genotyping is insufficient5,6.

If pathogenic or modifying variants are incorrectly phased or missed altogether, patients may receive standard doses they cannot safely metabolize, leading to severe or fatal toxicity7. Here, incomplete genotyping directly translates into clinical risk.

CYP2D6: Structural Complexity Drives Misclassification

CYP2D6 presents a different, but equally challenging problem. As one of the most polymorphic genes in the human genome, it includes gene duplications, deletions, hybrid genes, and high sequence similarity to its pseudogene CYP2D73,8.

Without accurate haplotype resolution, patients may be misclassified, leading to under-treatment, therapeutic failure, or toxicity across a wide range of medications including antidepressants, opioids, and tamoxifen9.

Together, DPYD and CYP2D6 illustrate a central point: accurate pharmacogenomics depends on resolving both variant identity and chromosomal context.

Why Short-Read Sequencing Falls Short in Complex Pharmacogenes

Despite widespread adoption, short-read sequencing is fundamentally constrained by its reliance on DNA fragmentation. While effective for many applications, this approach breaks long-range genomic context into small pieces, making it difficult to reconstruct haplotypes or detect large structural events10,11.

In repetitive or homologous regions, short reads often align ambiguously, introducing mapping errors and dropped variants. In DPYD, GC-rich and repetitive regions such as exon 1 frequently show reduced coverage and unreliable variant calls12. Structural variants, including duplications or gene conversions, may be fragmented across reads and remain undetected.

The challenge is even more pronounced for CYP2D6, where near-identical pseudogenes often cause systematic misalignment. As a result, short-read workflows often require complex inference algorithms or orthogonal assays that can complicate analysis and application13.

In short, while short reads can identify variants, they often fail to explain how those variants function together.

How Long-Read Sequencing Enables True Pharmacogenomic Resolution

Long-read sequencing directly addresses these limitations by preserving long-range DNA information. By capturing entire pharmacogenes end-to-end in single reads, long-read platforms enable simultaneous detection of single-nucleotide variants, structural variants, and haplotype phase within one assay14.

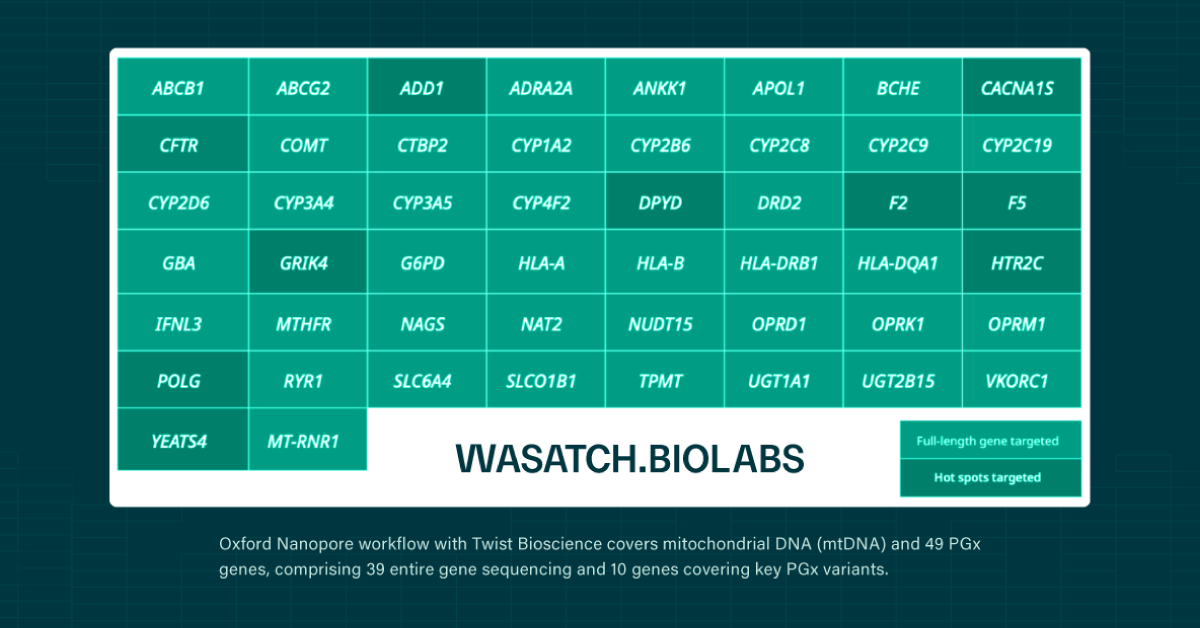

Oxford Nanopore sequencing, in particular, allows for long to ultralong reads15, making it possible to traverse complex loci such as CYP2D6 without ambiguity. In multiple studies, long-read approaches have resolved previously ambiguous diplotypes and uncovered novel alleles that short-read methods could not confidently classify11,16.

Crucially, long-read sequencing enables direct haplotyping without reliance on family data or statistical inference. This simplifies workflows, improves confidence in genotype assignment, and results in more reliable phenotype predictions, the ultimate goal of pharmacogenomics.

Clearer haplotypes translate into safer dosing, reduced adverse events, and more predictable therapeutic outcomes17.

Conclusion: From Genotype Lists to Actionable Drug Guidance

Full-gene pharmacogenomics represents a shift from variant cataloging to functional interpretation and prediction of drug responses. By capturing variants, structural complexity, and haplotype context in a single assay, nanopore long-read sequencing provides a clearer, more actionable view of how patients metabolize medications.

While short-read methods remain useful, they struggle in precisely the genes where accuracy matters most. Long-read sequencing overcomes these barriers, enabling direct haplotype phasing, comprehensive variant detection, and higher confidence in clinical decision-making.

As long-read pharmacogenomic data becomes integrated into clinical workflows, its impact will extend across oncology, psychiatry, pain management, and beyond, bringing precision prescribing closer to routine practice and transforming how genetic information informs patient care.

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CA, Meulendijks D, et al. Translating DPYD genotype into DPD phenotype: using the DPYD gene activity score. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16(11):1275-1284.

- Taylor C, Crosby I, Yip V, Maguire P, Pirmohamed M, Turner RM. A Review of the Important Role of CYP2D6 in Pharmacogenomics. Genes. 2020;11(11):1295.

- Turner AJ, Derezinski AD, Gaedigk A, et al. Characterization of complex structural variation in the CYP2D6-CYP2D7-CYP2D8 gene loci using single-molecule long-read sequencing. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023;14:1195778.

- Pratt VM, Cavallari LH, Fulmer ML, et al. DPYD genotyping recommendations: a joint consensus recommendation of the association for molecular pathology, American college of medical genetics and genomics, clinical pharmacogenetics implementation Consortium, college of American pathologists, Dutch pharmacogenetics working group of the royal Dutch pharmacists association, European society for Pharmacogenomics and personalized therapy, Pharmacogenomics knowledgebase, and pharmacogene variation Consortium. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2024;26(10):851-863.

- Ambrodji A, Sadlon A, Amstutz U, et al. Approach for phased sequence-based genotyping of the critical pharmacogene dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD). International journal of molecular sciences. 2024;25(14):7599.

- Shrestha S, Zhang C, Jerde CR, et al. Gene‐specific variant classifier (DPYD‐Varifier) to identify deleterious alleles of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2018;104(4):709-718.

- Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase genotype and fluoropyrimidine dosing: 2017 update. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2018;103(2):210-216.

- Del Tredici AL, Malhotra A, Dedek M, et al. Frequency of CYP2D6 alleles including structural variants in the United States. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2018;9:350795.

- Hicks JK, Bishop JR, Sangkuhl K, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2015;98(2):127-134.

- Cicali EJ, Elchynski AL, Cook KJ, et al. How to integrate CYP2D6 phenoconversion into clinical pharmacogenetics: a tutorial. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2021;110(3):677-687.

- Tafazoli A, Hemmati M, Rafigh M, et al. Leveraging long-read sequencing technologies for pharmacogenomic testing: Applications, analytical strategies, challenges, and future perspectives. Frontiers in Genetics. 2025;16:1435416.

- De Luca O, Salerno G, De Bernardini D, et al. Predicting dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency and related 5-fluorouracil toxicity: Opportunities and challenges of DPYD exon sequencing and the role of phenotyping assays. International journal of molecular sciences. 2022;23(22):13923.

- Chen X, Shen F, Gonzaludo N, et al. Cyrius: accurate CYP2D6 genotyping using whole-genome sequencing data. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2021;21(2):251-261.

- Ammar R, Paton TA, Torti D, Shlien A, Bader GD. Long read nanopore sequencing for detection of HLA and CYP2D6 variants and haplotypes. F1000Research. 2015;4:17.

- Jain M, Koren S, Miga KH, et al. Nanopore sequencing and assembly of a human genome with ultra-long reads. Nature Biotechnology. 2018/04/01 2018;36(4):338-345. doi:10.1038/nbt.4060

- Tilleman L, Rubben K, Van Criekinge W, Deforce D, Van Nieuwerburgh F. Haplotyping pharmacogenes using TLA combined with Illumina or Nanopore sequencing. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):17734.

- Roses AD. Pharmacogenetics and drug development: the path to safer and more effective drugs. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2004;5(9):645-656.